The attackers exploited a reentrancy vulnerability in the Orion Protocol's core contract, ExchangeWithOrionPool, by constructing a fake token (ATK) with self-destruct capability that led to the transfer() function.

This blogpost focuses on Demystifying Smart Contracts & Auditing and is the first part of the audit course. See primer here.

Definition of Smart Contract (feel free to skip :p)

A smart contract is a software program written in a contract-oriented programming language such as Solidity. The beauty of a smart contract lies in its ability to operate autonomously without the need for a central authority to oversee its processes. This means that once implemented, the contract can run without human intervention and enforce its terms autonomously.

Some more redundant stuff; expand to get a refresher on the basics

Smart contracts can interact with other contracts, users, or external systems through APIs. They are able to receive and process inputs by performing computations, access and update data stored on the blockchain, and trigger events based on predefined conditions. The code within the smart contract can include conditional statements, loops, and data structures to handle complex logic and decision-making. Different blockchains and blockchain ecosystems use different languages to write smart contract code. For example, Solana uses Rust, Cosmos uses Go or Rust, Bitcoin uses scripts, and Ethereum uses Vyper or Solidity.

This article series is targeted to an audience comprising of seasoned blockchain security professionals.

As discussed in the primer blog, we at BlockApex Labs have picked the flag to lead the standardization of an advanced knowledge base for blockchain security.

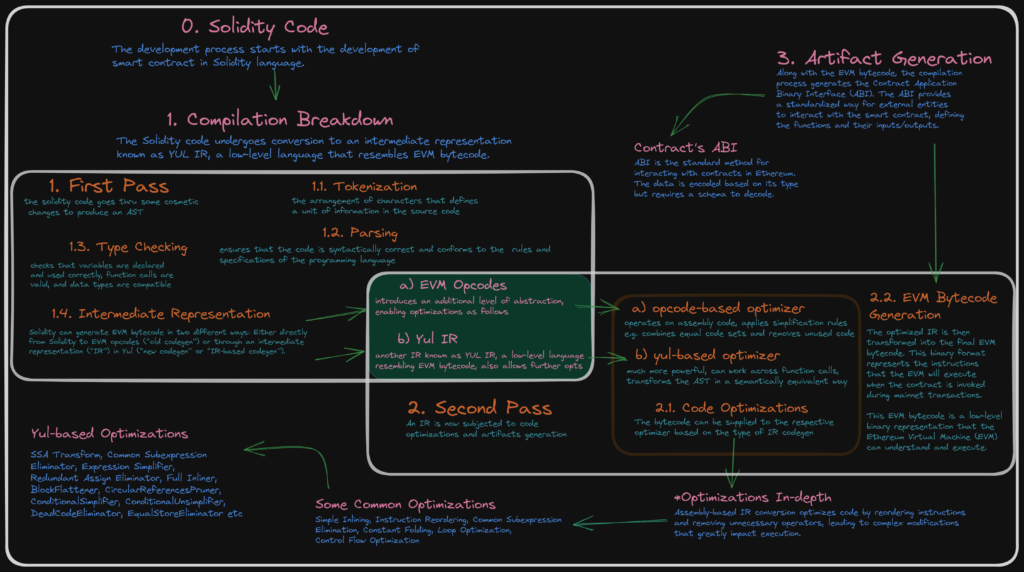

It is now common knowledge that Solidity is a contract-oriented programming language used to write smart contracts on Ethereum Blockchain, so let’s start and ponder over the several phases a solidity smart contract goes through before its equivalent bytecode is generated and is ultimately stored on the EVM.

The process begins with the developer writing Solidity code. This code can be written in the Solidity programming language and may contain bugs, vulnerabilities, or other syntactical, semantical, logical, or run-time issues.

The Solidity compilation process involves several stages of transformation, analysis, and optimization, resulting in the final EVM bytecode that is stored on the Ethereum network. The steps of the Solidity compilation process are susceptible to manipulation, and an advanced adversary can exploit them for personal gain.

Rememeber, an adversary/ malicious actor with an advanced knowledge set can cause harm to the system as all of the stages mentioned hereon are prone to manipulation.

Solidity code goes through two main passes during compilation: the first and second phases.

The first pass of the compilation process involves the following steps:

During the first phase of compilation, which is lexical analysis, the Solidity code is tokenized, broken down into a series of tokens (the arrangement of characters that defines a unit of information in the source code), which includes individual words, symbols, and operators. This step helps identify the fundamental elements of the code as defined in the Solidity Lexer.

The tokens are parsed to generate an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), representing the structure of the Solidity code in a hierarchical manner. This step ensures that the code is syntactically correct and conforms to the rules and specifications of the Solidity programming language defined in the Solidity Parser. The steps involved are; noting syntax errors, helping in building a parse tree, acquiring tokens from the lexical analyzer, and scanning for syntax errors, if any.

The AST is subjected to type checking, where the compiler verifies that the code follows the type rules defined by Solidity. It checks that variables are declared and used correctly, function calls are valid, and data types are compatible. Type checking helps identify type-related errors and ensures type safety within the code.

Solidity can generate EVM bytecode in two different ways: Either directly from Solidity to EVM opcodes (“old codegen”) or through an intermediate representation (“IR”) in Yul (“new codegen” or “IR-based codegen”).

The second pass of the compilation process involves code optimization and artifacts generation.

The bytecode can be supplied to the respective optimizer based on the type of IR codegen, either the EVM opcode or the Yul IR codegen. The “old” optimizer operates at the opcode level and the “new” optimizer that operates on the Yul IR code.

Some of the common compiler optimizations utilized by both modules are discussed below.

Compiler Optimization Techniques

Following the conversion to an assembly-based IR or the Yul-IR, the code again undergoes optimization techniques such as reordering instructions, removing irrelevant operators, etc. These optimizations go beyond simple transformations and delve into more intricate modifications that can significantly impact the execution of the code.

Some of the commonly employed techniques at this stage are:

The compiler strives to extract maximum efficiency from the assembly-based IR by employing these advanced optimization techniques. Each optimization is carefully designed to minimize unnecessary computations, memory access, and branch instructions, ultimately resulting in highly optimized code that can be executed more rapidly and efficiently on the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM).

Once the IR is optimized, either assembly-based (EVM opcode) or Yul IR-based, it is transformed into the final EVM bytecode. The EVM bytecode is a low-level binary representation that the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) can understand and execute. It consists of instructions and data representing the smart contract's behavior and logic.

What happens once the solidity code is finally converted into its final form of EVM Bytecode will be covered in the article series and in-depth in the Smart Contract Security Auditing 401 by BlockApex.

Let's remember for now that until the smart contract is deployed, the attack windows are shaded. This means that a malicious actor cannot view the contents of a legitimate protocol.

However, the tables turn once the EVM bytecode is formed and the smart contract goes live.

Along with the EVM bytecode, the compilation process also generates the Contract Application Binary Interface (ABI). The ABI provides a standardized way for external entities to interact with the smart contract, defining the functions and their inputs/outputs.

Solidity code is part of a larger system, i.e., the blockchain. Blockchains are of adversarial nature; participants can engage in strategic and competitive actions to gain advantages or exploit vulnerabilities.

For instance, participants can observe pending transactions and choose to exploit this information by engaging in front-running or sniping activities, attempting to execute their own transactions ahead of others.

It's important to note that the components of the blockchain system can be manipulated if individuals possess advanced and appropriate knowledge to do so.

Let’s look at a blockchain's components and how they may be manipulated.

Malicious actors can exploit vulnerabilities in the consensus algorithm to gain control over the network or disrupt the consensus process via various types of attacks such as 51% attacks, selfish mining attacks, double-spending attacks, etc.

Manipulating the transaction pool can involve prioritizing certain transactions over others or spamming the pool with invalid or malicious transactions by

Malicious actors can manipulate block creation by creating invalid blocks or withholding valid blocks to perform selfish mining attacks

Smart Contracts are prone to vulnerabilities in code and logic. Or the execution environment can be tested to perform attacks such as reentrancy attacks or integer overflow attacks, which can lead to unauthorized access, financial losses, or unintended consequences.

Forking can have ill intentions, such as performing double-spending attacks, altering transaction history, or manipulating the consensus algorithm.

Network protocols can have various types of attacks,

such as Sybil attacks, eclipse attacks, and routing attacks.

Vulnerabilities in the node software can be exploited to perform various types of attacks, such as denial-of-service attacks or remote code execution attacks.

Miner Extracted Value (MEV) is performed at the expense of other users via Uncle-bandit attacks, time-bandit attacks, sandwich attacks, or frontrunning and backrunning attack.

Malicious actors can exploit governance mechanisms to introduce malicious changes, manipulate decision-making processes, and control the network for personal gain.

In the adversarial ecosystem of Blockchain, each interaction stage has seen several exploits over the span of time. These attack windows can be made vulnerable by an actor having a higher knowledge set. For a blockchain security researcher, it is vital that these stages are never hidden from one’s PoV.

Smart Contracts Hold Valuable Data

If you’re following the blog by now, you must be quite familiar with the idea of smart contracts.

Smart contracts hold valuable data. The term "valuable data" refers to information that has inherent worth, whether it is in the form of financial assets, digital assets, intellectual property, personal information, or any other type of data that holds value to individuals or organizations.

The valuable information that smart contract hold includes, but not limited to, are Tokenized assets, financial information, digital property, intellectual property, personal and identity data, supply chain and logistics data, and data marketplaces.

Why protect smart contracts from the start?

We are aware that smart contracts have the primary purpose of executing agreements and removing intermediaries; they are immutable, and most importantly, they hold valuable data. Yet they are written and designed by humans. People like you and me are very much capable of making mistakes, so a need arises that the development of such crucial components of the blockchain ecosystem is made secure by design.

Why is that? A couple of key reasons that prove effective are as follows.

Immutability of Deployment: Once a smart contract is deployed on the blockchain, the code is essentially immutable. Therefore, ensuring the contract's security before deployment is crucial to mitigate any potential risks.

Permissionless Nature of Interaction: Smart contracts operate in a permissionless environment; this means that adversaries and potential attackers also have unrestricted access to the contract's code.

Considering the above factors, malicious actors can scrutinize the contract for vulnerabilities, attempt to exploit weaknesses, or launch attacks to extract rewards or disrupt the contract's functionality. It is essential to proactively secure the contract to protect it from such adversarial actions.

We hereby conclude that developers are responsible for making their smart contracts secure by default, and therefore, they must take measures to identify and address potential security risks during development.

In a nut shell (TL;DR)

Blockchain technology offers more than just decentralization and addresses the limitations of centralized systems. Smart contracts, which are pieces of code stored on the blockchain, automate and execute agreements without the need for intermediaries. They provide efficiency, security, and transparency. However, smart contracts and the components of the blockchain ecosystem are prone to manipulation and vulnerabilities at the finer steps of their execution.

Smart contract auditing is crucial to identify and address these vulnerabilities, ensuring the security of valuable data held within smart contracts. Auditing helps developers protect user funds, maintain contract integrity, and foster trust in the blockchain ecosystem. Thorough security audits and best practices during development are essential to make smart contracts secure by default and prevent the challenges of fixing bugs once deployed on the immutable blockchain.

The attackers exploited a reentrancy vulnerability in the Orion Protocol's core contract, ExchangeWithOrionPool, by constructing a fake token (ATK) with self-destruct capability that led to the transfer() function.

On the surface, the GameFi industry sounds revolutionary. However, digging a little deeper reveals several questions about its legitimacy. What are the risks associated with its play-to-earn model? Are all games which claim to be a part of GameFi credible? And, at the end of the day, is this a viable direction for gaming, or nothing more than a short-lived gimmick?

An off-chain transaction deals with values outside the blockchain and can be completed using a lot of methods. To carry out any kind of transaction, both functioning entities should first be in agreement, after that a third-party comes into the picture to validate it.

What was essentially the biggest hack in the history of cryptocurrency became a valuable lesson on the importance of security and just how powerless big organizations can become in the face of powerful hackers. The unusual trajectory of this incident also begs the question of where to place the blame in these kinds of attacks. Read more to find out exactly how the hack took place as we analyze the most pressing questions surrounding this attack.

BlockApex (Auditor) was contracted by Voirstudio (Client) for the purpose of conducting a Smart Contract Audit/Code Review of Unipilot Farming module. This document presents the findings of our analysis which took place on _9th November 2021___ .

Over $720M worth of funds were stolen this month, illuminating a dangerous message about the security and reliability of these platforms- raising several questions. Is orchestrating an attack of this level really so easy? If I happen to be a daring individual with the right technical skills, can I too be the owner of millions of dollars worth of funds? And most importantly, what measures can other platforms take beforehand to ensure they and their users are safe from becoming the next target?

Beanstalk protocol got hacked for around $74M through exploiting the governance mechanism & stealing all the BEANS & Curve LP tokens stored in the Beanstalk protocol.

A major pillar of blockchain technology is transparency. This means that any system built on blockchain is by definition public- a fact that introduces an entirely new set of vulnerabilities and threats. As a result, cleverly orchestrated hacks on blockchain solutions are not an uncommon feat. Even the biggest names in the field continue to suffer from attacks, resulting in losses equating to millions of dollars.

Borderless Money is a decentralized finance protocol redefining how Social Investments are made, using yield-generating strategies and contributing to social causes. An open, borderless digital society, with borderless money, where the goods, services, technology, information, opportunities, and capital can flow through the borders from one hand to many, fairly, transparently.